How the Police Files from the Uyghur Detention Camps Reveal China's Understanding of Human Rights

The leak of the Xinjiang Police Files has provided the best evidence to date of what many experts believe is an ongoing genocide against millions of Uyghurs in China. Read more about these files and what they tell the world about China's views on human rights.

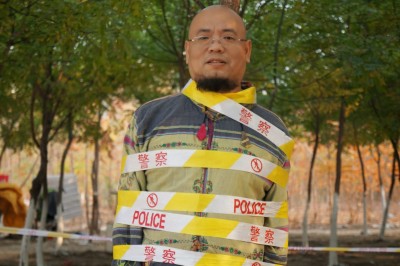

Dr. Adrian Zenz: "Probably the largest incarceration of an ethnoreligious minority since the Holocaust." / Picture: © Wikimedia Commons / Smileycharity, CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

Dr. Adrian Zenz: "Probably the largest incarceration of an ethnoreligious minority since the Holocaust." / Picture: © Wikimedia Commons / Smileycharity, CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

For years, various individuals, organizations, and Western nations have accused the Chinese government of numerous human rights violations, including the mass detention and potential genocide of its Uyghur Muslim population in Xinjiang province.

With the release of the so-called Xinjiang Police Files, the claims of atrocities being carried out against the Uyghur population in China seem to have been confirmed.

Although China continues to deny that it is committing human rights violations and insists that the Uyghurs are attending voluntary vocational training, these leaked files provide severely damning evidence to the contrary. The disturbing files have shed new light on the Chinese government’s twisted interpretation of and lack of respect for human rights.

German anthropologist and Senior Fellow in China Studies at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation Dr. Adrian Zenz, who has been researching the detention of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang for years, recently obtained and published the files.

Dr. Zenz claims he obtained the files from a source that hacked into computer systems of the Public Security Bureau (PSB) of the Konasheher and Tekes counties–both regions traditionally dominated by ethnic groups. The source of the files wished to remain anonymous for safety reasons.

In addition to being analyzed and authenticated by Dr. Zenz and his team, the files have been peer-reviewed by other scholarly researchers. Additionally, investigative research teams from numerous reputable media outlets–including Der Spiegel, Le Monde, and the BBC–have also analyzed, authenticated, and reported on the files.

What’s in the files?

The Xinjiang Police Files are a cache of tens of thousands of files, including speeches, images, documents, and spreadsheets that document China’s atrocities against the Uyghurs. Disturbingly, the files include thousands of mugshots of detainees, photos of tactical police forces conducting anti-escape drills, pictures of detainees being forced to watch propaganda under the supervision of guards with clubs, pictures of guards interrogating detainees in “tiger chairs,” and images of guards carrying out forced injections on handcuffed detainees.

In addition to these disturbing images, the files also include satellite images that confirm that construction of the camps began in 2017, the camps have a high exterior wall with multiple watchtowers, and the camps are guarded by hundreds of police officers, including heavily armed “special police units.”

The faces in the #xinjiangpolicefiles are a reminder of the international community’s responsibility to protect the millions of #Uyghurs interned in the camps.

— World Uyghur Congress (@UyghurCongress) June 22, 2022

We must always remember them. pic.twitter.com/UrTf0Ox4Ho

As mentioned above, the leaked files do not only include images. There are also thousands of documents, spreadsheets, and internal communications–some of which are linked to senior officials in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

In a press release, Dr. Zenz even suggested that the files point to the “personal involvement” of President Xi Jinping.

The documents discuss the use of intimidation, handcuffs, blindfolds, shackles, and even deadly force on detainees. Although one speech from 2017 refers to the detention camps as “humane,” the same speech suggests that detainees “must not be let out” because the “reeducation” may not have worked.

Despite China’s repeated denials, the extensive cache of images, lists of guards and detainees, detailed instructions for running the camps, and internal communications from high-ranking officials paint a very disconcerting picture of what is happening to an estimated 1-2 million Uyghurs in China.

The files seem to corroborate what Dr. Zenz uncovered in his years of research and described in a 2020 article as “probably the largest incarceration of an ethnoreligious minority since the Holocaust.”

Below is a short video of Dr. Zenz summarizing the significance of the files:

Corroboration of personal stories

While the files corroborate years of research done by Mr. Zenz and others, they are also consistent with first- and second-hand accounts of the atrocities.

One Uyghur man explained that, after he returned to China from his studies in the U.S., he was detained, hooded, and handcuffed. Similarly, Omir Bekali described his experience of being taken into custody by five police officers, handcuffed, hooded, and cramped in a prison cell with thirteen other Uyghur men. The incidents described by these two individuals match with the instructions laid out in the Xinjiang Police Files regarding how to handle detainees.

High-profile Uyghur activist Rushan Abbas also touted the Xinjiang Police Files as evidence of the warnings she has been making about the treatment of the Uyghurs for years. In 2018, six days after Abbas spoke about the atrocities against Uyghurs during a panel discussion about China’s “war on terrorism,” she reported that the Chinese government had detained her sister, Dr. Gulshan Abbas.

Following her sister’s detainment, Abbas only intensified her activism on behalf of the Uyghurs. In 2019, she continued to raise the alarm about a genocide against the Uyghurs and the arrest of her sister at the Amerika Haus Wien (America House Vienna). She also starred in the documentary “In Search of My Sister,” which was screened in November 2021 in Vienna. The film follows her activism and her mission to find and free her sister.

Three years after her sister’s disappearance, the Chinese government finally admitted that she had been arrested on charges of “terrorism.” Rushan Abbas, the two detainees mentioned above, and thousands of other Uyghurs like them have pointed to the Xinjiang Police files as proof that their stories about the mass detention and genocide of Uyghurs in China are not “Western propaganda” as others have claimed.

“The Xinjiang Police Files” offer significant new insights into the #UyghurGenocide.

— Rushan Abbas (@RushanAbbas) May 24, 2022

Documents provide the strongest evidence to date for a policy targeting any expression of #Uyghur identity, culture or religion.#FreeGulshanAbbas @TheJohnSudworth https://t.co/bkFgWu7mMo

China’s denials & visit of UN Commissioner

Obviously, the Chinese Communist Party, under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, has denied that it is committing human rights violations.

After initially denying the existence of the camps, the government now maintains that the Uyghurs are mostly attending voluntary vocational training, with some being sent there for “deradicalization.”

Even after the leak of the files, the Chinese government still asserts that reports of mass internment and genocide are simply Western propaganda and fearmongering against China.

The government will often cite an increase in the Uyghur population as proof that this is not happening, as is exemplified in the following tweet from the Chinese Embassy in Vienna:

Basic #facts about #Xinjiang's population, income, education and freedom of religious belief. pic.twitter.com/9j3w3B41sw

— Chinesische Botschaft in Österreich (@chinaembaustria) May 29, 2022

Chinese government entities like the embassy in Vienna will also post videos or pictures from Xinjiang that suggest that the Uyghurs are living happy and peaceful lives there. This can be seen in another tweet from the embassy below:

#Xinjiang enjoys a stable&secure society. Population of the ethnic groups is experiencing healthy&balanced development. Over the past 60+ years, the population increased fourfold and the Uyghur population grew from 2.2 M to about 12 M.

— Chinesische Botschaft in Österreich (@chinaembaustria) March 28, 2022

A glimpse of daily life in a kindergarten pic.twitter.com/JTVzcsZivC

The Chinese Communist Party continued to deny independent media or members of human rights organizations unrestricted access to the camps for years.

Rather than allow outsiders to verify or debunk the claims, the Chinese government simply wanted the world to take its word for it.

However, on the day of the release of the Xinjiang Police Files, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet was on a visit to China–the first by a Human Rights Commissioner in 17 years.

High Commissioner Bachelet met with various Chinese officials, including President Xi and other high-ranking officials from Xinjiang.

According to the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation (ORF), President Xi defended China’s human rights record in a conversation with Bachelet, saying, “Human rights issues should not be politicized, instrumentalized, or treated with double standards.” He also told her, "China’s human rights development fits in with national conditions.”

While many people had hoped Bachelet’s visit to the region would include unrestricted access to the camps and shed more light on the internment of Uyghurs, the High Commissioner concluded her trip with only a statement of vague concerns about human rights abuses in China and stated that her trip was “not an investigation.”

Following Bachelet’s trip to China, she faced heavy criticism from human rights advocates, Uyghur activists, and other governments.

Many feared her trip would be used as propaganda by the Chinese government to defend its human rights record without allowing a full investigation. In light of the increased criticism, Ms. Bachelet announced she would not seek another term as High Commissioner for Human Rights.

International reaction

Western countries, international organizations, and other advocacy groups have been voicing concerns about the mass detention of Uyghurs and other human rights violations in China for years and have repeatedly called upon China to allow independent investigators to have unrestricted access to the detention centers.

The U.S. has repeatedly raised the alarm about what is happening in Xinjiang. In January 2021, then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo officially recognized what is happening to the Uyghurs as a genocide. The Biden administration did not differ in its assessment of the situation and announced sanctions on some Chinese officials in response. Additionally, the US government has passed the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act to ensure that American entities are not funding forced labor in China.

Today, I signed the bipartisan Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. The United States will continue to use every tool at our disposal to ensure supply chains are free from the use of forced labor — including from Xinjiang and other parts of China. pic.twitter.com/kd4fk2CvmJ

— President Biden (@POTUS) December 23, 2021

Also Austria has strongly condemned China for what it views as human rights abuses.

In 2019, Austria’s Permanent Representative to the UN Geneva (and later President of the Human Rights Council), Elisabeth Tichy-Fisslberger, signed a letter to the President of the Human Rights Council with 21 other ambassadors calling on China to respect its human rights obligations and allow international observers to independently assess the situation.

Later, in 2021, the Austrian Parliament’s Human Rights Committee unanimously called upon Foreign Minister Schallenberg to condemn China for its treatment of the Uyghurs.

The number of countries that have spoken out against China’s atrocities against the Uyghurs has only increased over time.

Following High Commissioner Bachelet’s recent visit to China, 47 countries (mostly liberal democracies) issued a joint statement criticizing China for human rights abuses and demanding that High Commissioner Bachelet release an overdue report on the abuses in Xinjiang.

This statement echoes the sentiments of human rights experts at the UN and other organizations, including Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and many more.

While an increasing number of countries are coming out against China’s human rights abuses, there remains a significant number of countries that refuse to condemn and, in some cases, even support the Chinese government.

In response to the joint statement from the 47 countries mentioned above, nearly 70 countries issued a joint statement about respecting the sovereignty of other states and not interfering in their internal affairs.

The statement explicitly mentioned issues in Xinjiang as China’s internal affairs and sounded eerily similar to the comments by President Xi Jinping mentioned above. “We oppose politicization of human rights and double standards, or interference in China’s internal affairs under the pretext of human rights,” reads the statement.

The ongoing battle over human rights

The struggle between those that support human rights and those that do not has lasted decades, and there is no end in sight.

As China’s global influence has increased, its disregard for human rights has become more brazen. Unfortunately for supporters of human rights, the coalition of countries that do not support human rights is quite large.

In addition, many of them view the outrage from Western countries as insincere and hypocritical. These countries will often cite Western support for other human rights violators, such as Israel and Saudi Arabia, as well as their own violations.

Even with the disturbing testimony from Uyghurs and experts now being corroborated by the Xinjiang Police Files, the countries that support China are unlikely to hold it accountable for fear of also being held accountable for their own violations.

While these countries may have a point about the West’s hypocrisy on human rights, it does not change the fact that evidence suggests China is likely carrying out a genocide on millions of Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

Going forward, Western countries that claim to support human rights must not only criticize others but also lead by example. Maybe then they can convince other countries to join them in holding China accountable for its abuses just as they were able to garner enough support to hold Russia accountable for its brutal and illegal invasion of Ukraine.

How to react to the conflict of norms?

The fact that a populous Asian country with 1.4 billion people has to be run differently than, for example, Canada or Austria, is clear to anyone who has lived in China for a longer period of time and travelled through the country.

The cohesion of the huge empire of the largely apolitical Chinese people demands a certain strict and authoritarian leadership, which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) not only carries out, but furthermore - especially since the beginning of Xi's presidency - drives to "perfection".

At the latest since the necessary and violent last-minute suppression of the student protest movement at Tian'anmen Square on 4 June 1989 (liùsì shìjià), the Chinese government has regarded human rights as an existential threat.

Although China is a member of the Human Rights Council and - due to international pressure and for strategic reasons - incorporated human rights into its constitution a few years ago with the addition "The state respects and guarantees human rights", and has also formally ratified the most important human rights conventions of the United Nations (e.g. Universal Declaration of Human Rights), there has always been a major contradiction with the Western democratic interpretation of human rights.

Moreover, due to its political influence and funding of 12 per cent of the UN's mandatory contributions, Chinese diplomacy plays a key role in the UN Human Rights Council and helps set the agenda for global human development.

As Western reactions to the unprovoked Russian war of aggression against Ukraine show, sanctions at the economic level - prohibiting companies from doing business with certain Chinese companies - could also lead to a partial rethink. Western governments could, for example, cooperate more closely with regard to technology policy on the rules for artificial intelligence (AI) and the development of the latest mobile phone generation 6G, and together prevent high-tech products from being misused for human rights violations by the authoritarian regime in Beijing.

The example of the genocide of the Uyghur ethnic minority in Xinjiang is only the tip of the iceberg. Human rights conflicts run right across the country, from the oppression of other ethnic or religious minorities (e.g. Falun Gong), to the fate of the Tibetans, and most recently the suppression of the democracy movement in Hong Kong.

The problem is exacerbated by the enormous political influence and economic dependencies that China has been building up for some years, especially in other developing and emerging countries, due to its financing and development policies. Indeed, the CCP uses this power in other developing countries to push through its interpretation of human rights in such a way as to create a "conflict of norms" at the global level.

To reject this malign influence and authoritarian model of governance, democratic and freedom-loving peoples should join together to oppose Chinese subversion of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the establishment of parallel or substitute norms.

After witnessing the horrors of the Holocaust, the world vowed: “never again.” Yet these words may ring hollow if the world continues to sit idly despite mounting evidence of what some experts have called “the largest incarceration of an ethnoreligious minority since.”